Top Ten Good Ideas Gone Too Far in Frontend Development

On Contrarian Views

I’m convinced that most bad ideas, code related or otherwise, started as life as good ideas. As for the good idea > bad idea meme template, as exemplified below, my in-depth memetic research indicates that it might have begun with this Animaniacs segment. The format has morphed over the years, but it maintains staying power because it reveals an essential truth: the human mind tends to go to extremes in its problem solving, applying solutions that work in restricted problem domains as a cure-all in cases for which they were never intended and in which they do not work so well.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the extremely optimistic fads that are ubiquitous in software development, where a solution that is great for some cases tends to grow to encompass a conglomeration of uses it may never have been well-suited for. The prime example of this, at least for many people, is Object Oriented Programming. The reasons for such growth curves may be interesting, but are not my subject here. Instead, what follows are my top ten highly opinionated examples of good ideas gone too far in frontend development.

Fair warning, however: most of the opinions you are about to encounter are highly unpopular and do not necessarily reflect the views of anyone, including myself, which is why I preemptively disavow everything I have written here. Just as our bodies replace our cells completely every seven years, or something, so may it be said that I am not the author of this rant. As a way of continually reminding the reader of this, I will be illustrating the rest of this post solely with images from r/imaginary network expanded.

To begin with then, let’s turn first to everyone’s favorite topic, choosing a tech stack.

10. Tools

Because there is such rapid innovation occuring in the field of frontend development, the decision of which frameworks, tools, libraries and systems in general to use is always significant. For good reason there is always a lot of discussion regarding what tech can do the best job. Therefore:

Good idea: researching the right tech for the job

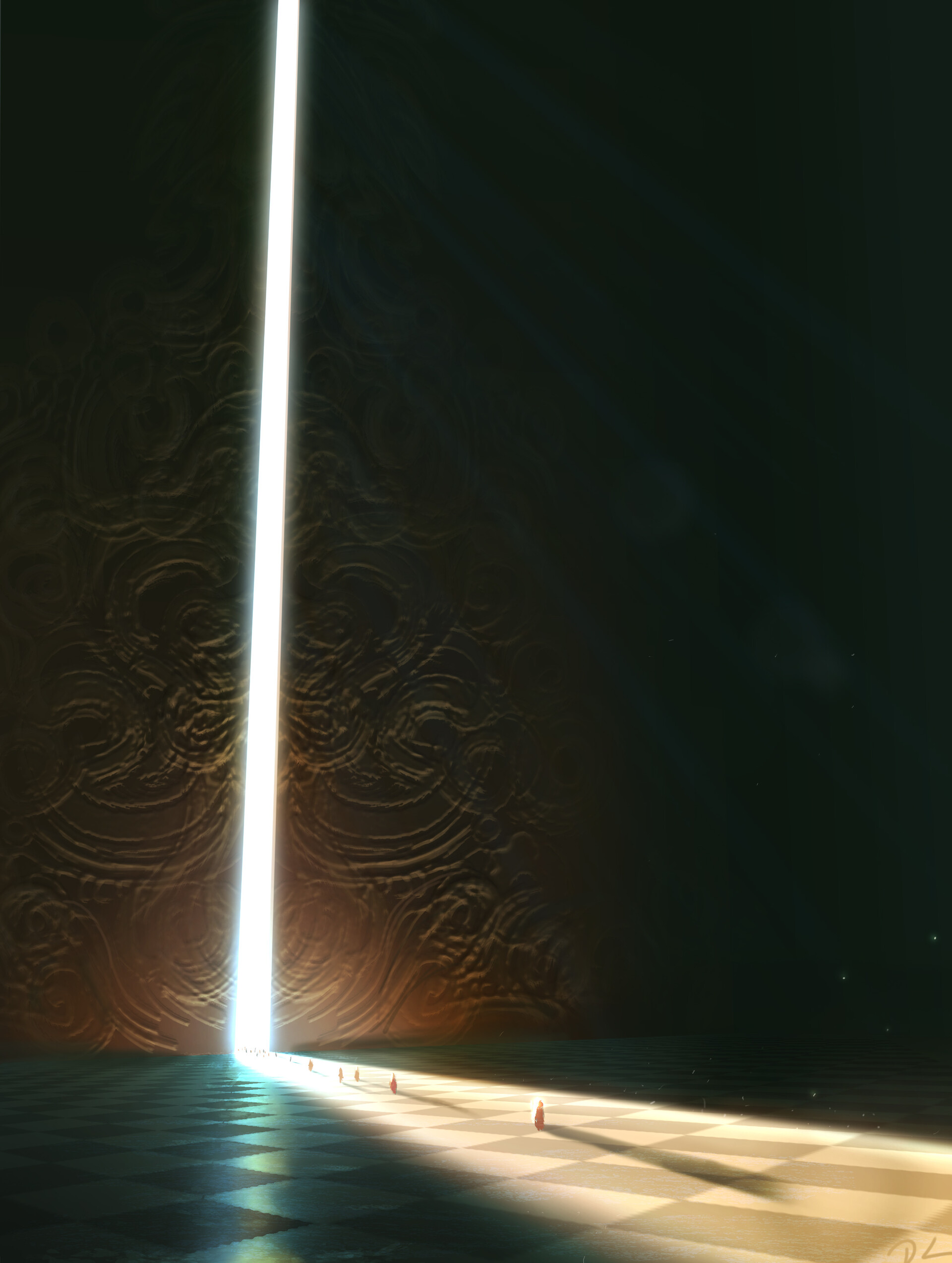

However, only in the most awesome of all imaginary worlds, the one depicted above—a world in which there are literally epic rotating contraptions of mysterious tomage— could we actually choose a tech stack without any regret, for there we would be able to simply swap it out for something more appropriate later.

In our sad, mundane world, without any real tomage in sight, it may be said of using tech X what Kierkegaard said of marriage, “use the newest library or don’t use it, you will regret both.” The reason for this is that complexity seems to be conserved, or at least the scope of a project will grow to match what we can accomplish reasonably quickly using the tools available. After all, it can’t be a coincidence that regardless of what tool is used there always seem to be serious problems and limitations with it.

Of course, that is not to say that the tech used doesn’t matter. It would not make sense to write an application of any size in jQuery alone in the present year. That would be generally recognized as uncool, and thus we should avoid it, while using a modern framework is generally recognized as, if not cool, at least reasonable. Critically though, beyond such generally accepted standards as this, there isn’t much that can be said for certain about what tech to use where. And moreover, there are always other considerations to bear in mind at any point in any product lifecycle. That’s why:

Bad idea: neglecting the social dynamics that will likely determine success or failure

As important as this is, I’ve put at number 10 since, although it is counterintuitive, I think most everyone, especially managers, already have an inkling of the truth of this. While a tech stack or a specific technology can provide a competitive advantage, and can make or break certain feature sets in certain deliverables, it is social dynamics that make or break entire organizations and products. That is because software development is embedded in these systems and the structue of resulting code arises from their communication patterns, as has been remarked on famously.

Trying to accomplish a particular technical outcome with tools that are not sufficient is doable, though annoying. It may take longer and be of lower quality in the end, but the most important asset, human capital, lives to fight another day. Trying to accomplish anything at all on teams that don’t work, or in which there are dysfunctional team dynamics, is not only difficult but leads to developer attrition and cycles of critical defects.

Perhaps this is because although code can become hardened and resistant to change it does not—aside from certain CSS positioning code—simply enact irreducible, unconscious habits. Nor does code become defensive when corrected. Instead, code just unwillingly respects the instruction set given to it.

For these reasons it would be unwise to expend undue attention all the time on technical questions or explanations of failure, to the extent they are excuses, as opposed to focusing on teams and management styles that help your organization reach is goals. And what is true of choosing tech is true, to a lesser extent, of all technical considerations in comparison to the human element of developer interactions.

The same is also true of culture. Without going into too much detail about what “culture” is or should be, since the best culture is very possibly different for different people, I would say only this: the importance of culture fit for everyone involved can’t be overstated. Culture is the health of an organization, and so its unwise to sacrifice it for any other good.

9. Rabbit Holes

So much for that which we developers have less control over. When it comes to things we have more scope to control individually, the next point is nevertheless like a microcosm of the last, since it too relates to the elevation of concrete observable states over processes. First, let’s begin with the obvious:

Good idea: concentration on observable results

No controversy here. Concentration is the only way to get anything done—concentration and its ever attendant familiar, coffee. But this raises a question. If concentration is good, wouldn’t it be even better to go into a rabbit hole, where there’s even more concentration on solving a problem? Of course, the idea sounds absurd. But trying to distinguish why turns out to be somewhat difficult.

What, after all, makes a rabbit hole a waste of time? We might say rabbit holes are characterized by some distinguishing factor: “no attention to context”, “repetitive failure”, or “duration of attempt”. But in normal problem solving it looks like these same phenomena just have a different name: “concentration”, “trial and error”, “being deeply involved”. About the only thing that really characterizes the rabbit hole is emotional valence (negative), but even that is not always the case, since normal problem solving can feel pretty annoying until it’s over, at which point there is satisfaction.

Nevertheless, we’ve all all been in rabbit holes, and we know they are distinct from useful concentration—in retrospect.

It seems to me that the whole problem here is that if a rabbit hole really exhibited such distinguishing features while we were in it, it wouldn’t be a rabbit hole. The disorientation inherent in the metaphor (Alice in Wonderland, it would seem) hints at the hypnotic effect of a puzzle that causes positive functions like concentration to progressively warp into negative ones like inattention to context, without our noticing the shift. At each point, the work bears a resemblance to actually getting things done, but in the end it occupies a different pole entirely.

Still, to me it seems that there is something to the concept of lost context as the distinguishing feature. It seems that this gets at the rabbit hole concept most accurately. A rabbit hole actually involves too much concentration on one facet of a problem, to the detriment of the overall work process. Hence:

Bad idea: focusing on observable results to the detriment of processes

To a certain extent, there’s no avoiding rabbit holes. It’s inevitable in daily development that certain problems turn out to be the most seriously consuming. If you take the Bhagavad Gita’s treatment of yoga as process-oriented metacognition seriously (I don’t know dude, sounds worth looking into), you might even say that part of not being in a rabbit hole is being undisturbed by being in a rabbit hole.

In more practical, day-to-day terms, perhaps the best thing we could do is just settle for not focusing too much on one part of the problem. A good way to avoid rabbit holes is therefore to make sure that your own work processes and rhythms are well defined and you regularly return to anchor points for context. I’ve found that taking regular breaks to step outside and evaluate what I am doing is the best way to ensure that incremental progress is actually being made, and that subproblems aren’t expanding but are actually well defined.

Aside from remembering where we are, it’s also important to keep in mind where we are going. There are different ways to maintain orientation toward the bigger picture, but for me this takes the form of diagramming whenever needed, so that the next stages are drawn out, defined, and tagged in the order they will be addressed. Other people might just prefer lists. Whatever the technique chosen, it’s worth sticking to it, so that you can notice when you are expending undue amounts of concentration on a subproblem.

8. Documentation

It’s absolutely true that the best documentation is code itself making sense. Well-chosen names, appropriate cut lines for functions, and sensible control flow structures all make code readable and easy to navigate. Therefore:

Good idea: using code that documents itself

However, there is still a place for comments and proper documentation—a fact it is easy to forget. The first person who ever said “documentation becomes stale” had hit upon one of the great rationalizations of all time. Do we even have evidence that it was not the voice of the devil? After, all it’s not wrong.

The problem here is that if documentation becomes stale, why explain your code at all since it will only increase confusion? Thus it became common for many developers to look at other’s code, and even their own code of yesterday, with a feeling akin to that depicted below, in a painting that might well be entitled “What’s a wegacy?”:

As can be seen, the practice of not adequately commenting harms not only those who code, but also the children, whose tender sensibilities can hardly appreciate the problems of variable naming. That’s why I would say:

Bad idea: not writing comments because “the code explains itself”

In fact, nine times out of ten, it doesn’t explain itself. And if it does, a comment can’t hurt. It is indeed easy for code comments to become outdated, but that is no excuse for not writing comments to explain your code. The question of whether a particular abstraction is an appropriate one for the task may depend on no more than whether or not there is a comment to explain it.

The thing is, it really doesn’t have to be this way. If working with Emacs has taught me anything, it’s that commenting your code can actually become second-nature. Whereas I would have previously been of the opinion that comments are for the otherwise surprising, unexpected elements of code, I now think comments serve a much broader purpose. They can act as a scaffolding over all abstractions, allowing the names in the code to be themselves more sparse when necessary, and explaining the whole algorithm as if it is surprising (which it invariably is, to someone who knows nothing about it).

I would not go so far as to call this approach “literate programming”. Instead, a look back at my code reveals that I actually practice what might be called semi illiterate programming. The approach has of course never really caught on for some reason.

At any rate, I think that to not comment more than we do is often to give ourselves too much credit: our algorithms may not be the best and even our future selves may not remember what precisely is going on in our code. For that reason it’s important to err on the side of documenting code. Think of the children.

7. Abstraction

We now come to two points, this and the following, which perhaps are the most arbitrary concepts here, as they concern largely stylistic considerations. These are mostly personal preferences about which disagreement is to be expected, but which inform many of the other ideas on this list.

The first has to do with abstraction and repetition. We all know how it important it is to keep it DRY, thus it said:

Good idea: not repeating yourself

But what I would add is that although this is an important principle of style, it isn’t the most important, at least to me. More important still is the idea of single responsibility, from which most other good style arises.

These two considerations (single form, through non repetition, and single purpose), may not always harmonize and we sometimes have to choose between them. If, for example, we have the choice of creating two components, or reusing one for two (slightly different) purposes, there are many different factors that come into play in determining whether to implement an abstract class or allow code duplication.

Of course, the goal should always be to determine the single purpose that is most generalizable. In theory, this single purpose, correctly articulated, should allow for a single form to represent it. But implementation details can get in the way of allowing this. In such cases we should be careful about what to avoid:

Bad idea: premature abstraction

Premature abstraction is dangerous because it seems like a good idea at the time. By the time this new abstraction is implemented fully, however, the various diverse purposes which it implements are so inextricably linked that they can never be separated out again without a complete rewrite.

Note that this is not the case for duplication. Code duplication can be rewritten, unless it is just tremendous amounts of duplication. Not only that but duplication, if the duplicated portions are idiomatic, is also understandable . When, however, an abstraction is introduced, it becomes subject to personal styles that may or may not be shared. It is also going to be an abstraction of varying degrees of appropriateness— is the abstraction really natural for the use case? Finally, is the abstraction’s intrinsic form, its own naming and implementation, obvious and natural? These are all considerations against premature abstraction, which make duplication of idiomatic code look almost like a relatively benign antipattern.

Duplication, at its worst, gets you halfway to the destination. But premature abstraction seems to me to be an actual wrong turn. Perhaps it is a stretch, but we can find analogues to this hierarchy through other parts of rhetoric, including fiction writing, where repetition is hardly frowned upon, but the idea of a single effect is almost always a good idea, at least if you buy Edgar Alan Poe’s theories. The comparison is, I think, not entirely irrelevant, which is why I am denoting code as a branch of rhetoric. The principles of limited human cognition are what we have to deal with in both cases.

Practically speaking, then, anytime there is an opportunity to abstract shared code I would suggest that the most important thing is to abstract out only what is truly shared in the logic of the two instances. To do that, we must have access to the whole repetoire of code sharing techniques. This may mean using inheritance patterns, but in Angular (with inheritance from component base classes being kind of awkward) it might mean a common parent component. It might mean sharing templates through ng-content outlets. It might mean sharing a pure .ts configuration object, or the implementation of a decorator pattern. Perhaps a common service can be injected, or component state can be moved into Redux.

Whatever is used to share code, the idea of just reducing repetition isn’t enough, we need to be sure that the way we are doing so makes sense, so that the abstraction is the essential one that matches the nature of the problem at hand.

6. Idioms

In the same vein of style comes another question, how to choose among programming idioms which are apparently equal for the job at hand. Here it must be said:

Good idea: using the latest and greatest tools

There is one issue, though, with the newest and fanciest tools. Sometimes they are just a highly specific implementation of things that could be done before. It is often the case, at least in Angular, that multiple tools are provided to accomplish the same job. Superficially, it can appear that these have different use cases. I think this is sometimes incorrect. In particular, I think that we should default to always using the tool that is more powerful, unless there is a reason not to:

Bad idea: using specific tools when more powerful, general tools are available

What does this mean? It is hard to express in every instance, but we can take one example: Angular forms. In Angular you can have either forms that are model driven or that are template driven. The typical explanation for which one to prefer goes as follows: model-driven forms, in which your form controlling code lives in the component’s Typescript, are for complicated forms, while template-driven forms are for forms that are simpler, since everything important happens in the template.

I wouldn’t say I exactly disagree, but as a matter of experience, what I have seen is that forms get more complicated as you go through time. And so what seemed like a good use case for a specific tool, the template-driven form, ends up getting refactored to be handled by the more powerful, general method (model-driven forms). It’s as if the whole domain specific language of template driven forms is a highly specific tool for certain cases that lacks generality. I mean, that is exactly what it is, since Typescript is Turing complete and whatever we do outside of that, inside of templates, can just be called configuration.

After long enough trying to make a complex model work with template driven approaches, it turns out that what you really wanted are your own specific idioms for dealing with the abstractions inherent in your own data model, and you might as well have gotten a head start on that by building it to begin with instead of trying any shortcuts using shallower domain specific language of the Angular template syntax.

It’s not just like this with forms though. In almost every case, with every library and with everything that promises to be a shortcut, it turns out that hard problems end up returning to “the ground language”, that is, the primary execution language. Let’s call it the PL, as opposed to the Domain Languages, or DLs, that build up around it. PL solutions are more verbose (sometimes) and often feel like reinventing the wheel, but they have the advantage of debugability, fine-grained temporal control (they can be hooked into the component lifecycle at will), and tighter correspondence to your own data model. They can also be consistent across multiple components, as well as transparent and well-understand.

As another example consider the idea of sending input to a component. In Angular the way to do this is through Input decorators, but this immediately raises the question “how many inputs?” Take a moment to consider how many inputs are appropriate for different levels of component complexity.

If you said a component needs more inputs the more complicated it becomes, that is an example of Domain Language orientation. If you think a component should get fewer inputs the more complicated it is, that is PL orientation.

Clearly, I hold a candle for the second view. If, for some complicated component, the configuration can be made a result of inspecting a single, complex configuration object passed down through a single input, then as little as possible will depend on the template language—everything is moved to the Typescript. In this case, everything about your configuration object lives in the component code. This means that you can assemble the configuration object as a whole in the parent code and respond to changes to it singularly in the child’s update function. It means that now you can do configuration changes that refer to other parts of the configuration—a common requirement. When you render out a subproperty of the configuration object, even change detection will happen predictably, based on reference in accordance with object equality rules in the primary language.

There are thus a huge number of advantages to handling problems in the primary language, because it is always the most versatile and powerful. And this doesn’t even address the benefit of syntactic simplicity, of reduced cognitive overhead: there is but one language in which solutions are expressed, and that language is consistent.

Of course, PL solutions should be tempered. It is more of an orientation to return problems to the Typescript before they become larger. And it suffers from one main problem: PL solutions can be non-idiomatic. Because you are effectively escaping Angular and the Angular way of doing things, the solutions require some explanation. But it is a general outlook that seems to me to make sense and also be applicable outside of just this area as well.

5. Transpilation

Moving from style and back to process, the following two points have to do with what is objectively the most broken aspect of frontend development, the build chain. It is not that there aren’t awesome tools for helping us manage the build chain, the problem is that it is necessarily just very messy. It’s hard to imagine a way of truly configuring it in a single place.

Not knowing about any other deployment environments in depth, what I am speaking about is just my own feeling. Nevertheless, I think that the frontend build chain has many steps more than anyone would really want. One reason for this is the tension between new language features and the sometimes ardous methods we have of shoehorning them into our development process. First off:

Good idea: using the newest language features

Everything ES6, for example, is an improvement, hands down. However:

Bad idea: transpilation

What? How can that be? Transpilation is like the air, the sea, a part of our world. As long as the sun as shone, so has transpilation been with us, like war. That may be true, but there have always been those few who, wandering from town to town as itinerant build engineers, speaking in whispers, await a day when the refinement of language may take place in other ways— via hygenic macros for instance.

Of course it’s been done before. It was done that way by the ancient ones. The idea of adding language features in a composable way, in a sensible way having nothing to do with transpilation, and in a way which can be easily reasoned about, is probably as old as Lisp.

But will we ever see an end to transpilation? No. The reason we will always transpile is that as soon as one feature set stabilizes and is supported by all browsers, it’s likely another will be defined, but not yet implemented everywhere.

And what about WebAssembly, you say? Is there any chance that it can help us? Apparently not likely, since studies indicate that 100% of developers who use WebAssembly regularly are actually just the same five Ukranian orphans working in an abandoned paint factory.

Nevertheless, even though transpilation is here to say, since I needed ten things on this list, I decided to include it. It is truly awkward.

4. Build Tools

I like using Angular CLI to create the initial project files and to add new components and services to a project. Who wouldn’t? There is too much boilerplate to make doing all that on your own sensible, and producing all those files at once fills me with warm fuzzy “getting things done” feelings. Therefore:

Good idea: using generators for creating components and services

But let’s not beat around the bush here. Let’s not avoid the elephant in the room. Let’s frankly admit it: generators like Yeoman were around before Angular CLI. Angular CLI has bigger dreams. It aims to replace Webpack by wrapping it in a simplified interface. And my question is: why?

I think Angular CLI does a great job of getting projects off the ground. I just have some reservations. Why would anyone think that the whole build chain itself even falls in the purview of the frontend framework? How could it ever be that a brand new configuration, in the Angular.json file, with all new semantics and all new way of doing things, could possibly replace the build system that has been worked out completely already to meet all use cases? The imperialism of Angular CLI’s goals are a little reminiscent of how the Angular team already built their own html parser, because Angular’s templates are not standards compliant.

Bad idea: turning the whole build into a black box

That’s why I suspect that if you are engaged in enterprise-level development with Angular you’ve probay already ejected the Webpack config from your Angular project, and if you haven’t, you probably will. There’s just no reason to think this black box Angular CLI build tool can replace other tools that have been around for longer and have been evolving communally to deal with every conceivable issue, when the build chain touches so many unforseen possibilities unrelated to Angular.

Of course, it would be awesome if Webpack were simpler. But part of the complexity of Webpack configurations is not incidental, it’s a product of the previous point: the FE build actually has a lot of steps and a lot of considerations go into it. As it is, Angular CLI is a stepping stone, it’s what you use to get started. But when, as they say, the coconuts start dropping, you’re going to switch back to Webpack.

3. Frontend Testing

There’s really no way to sleep at night without automated testing, and for that reason we have to say:

Good idea: testing

The question of how to do testing is more open, however. There may be no perfect testing paradigm for all cases, but one thing for certain is:

Bad idea: unit testing everything in sight

Note the key word “unit”. End-to-end testing is completely fine, in fact it is so far and away superior for testing Angular compared to using Angular’s built-in unit testing tools that there is almost no comparison. If unit testing Angular with Angular testbed is like banging rocks against the ribcage of a wooly mammoth in hope of rain, using Puppeteer for testing is like atomic energy, and Cypress.js is like powering your spacecraft with exotic dark matter.

The distinction to make here—the reason why end-to-end testing is so much better—is between two distinct types of function. For one set of functions unit testing is a good idea, but for the second it has been taken too far

The unit testing paradigm has for its ideal cases the classical algorithm. In this sense a classical algorithm is one that returns a set of predefined output for a set of predefined input. Crucially, the input can be simulated across a range, continuously or with some logical, but limited, number of discontinuities.

Because there is a coherent range of input for such programs, there is a high ROI for writing tests: write one test, feed it multiple inputs. Think of testing an algorithm that tests primality. Regardless of the complexity in implementation, all that we have to do is feed it input from a table of known primes, and then inspect the results. Different prime classes can form some implicit discontinuities, but at the end of the day the “input range” is a real concept. The range of inputs is simulateable without much trouble.

The frontend is nothing like this. It is event based in that there are many pathways a user can walk. Instead of a range of discreet inputs, its test data is really a bunch of on/off switches existing somewhere on a branching timeline. Its return value is an amalgam of business data (rendered variables) and program data (the DOM itself). In terms of set up and tear down, it exists in a very hostile environment for pure testing (the browser). All in all, I think we can say it has a different function shape.

Someone who knows more mathy things than me could give a name to what kind of function it is, but it is not the kind of more or less isomorphic input/output set produced by classical algorithms. Of course they are not totally different. They are both deterministic, but that really doesn’t say much in practical terms.

Because the state shape as it changes over time is much more complicated (see the next point below, on dealing with state), and because it incorporates DOM related entities, the production of test data and the verification of test output is also more involved. Unit testing Angular involves a great deal of mocking components to account for dependency injection. And because the meaningful test input is not a range, what you’ve gained after the time consuming process of mocking a component is not usually the ability to test multiple scenarios, but only the ability to test the next scenario that you explicitly reproduce.

Finally, another weakness of unit testing is that the scope of unit tests is limited to that subset of the system that you have completely mocked. Only when smaller units have been tested can larger parts be tested, regardless of where in the system failures tend to occur.

Luckily, there is a better way. First, it is possible to focus on unit testing the reducers of the Redux portion of an application. This removes many problems and matches better the ideal use case for unit testing. More generally though, until we know more about how to characterize the frontend as a function (by adopting the purely functional approach of something like Elm) the best thing to do is E2E testing. E2E testing effectively “collapses” the state representation into a family of states that look the same at any point to the user or webdriver.

E2E testing avoids complicated reproduction of the dependencies for tested components, by testing what the user actually sees. It also makes intermediate and high-level abstractions testable immediately. By testing the final appearance and structure of the rendered page, including the routing and behavior as all components tie together, the test suite can take a top-down approach to verifying behavior.

E2E also has a second benefit: it looks at things in a different way. A unit test, written in Typescript and testing properties in Typescript, looks at things the same way the developer does when initially attempting to guarantee correctness. An E2E test has the advantage of remaining agnostic regarding the internal implementation.

As another side benefit, the time saved by not mocking dependencies for unit testing frees us up to write unit tests only for the algorithmic portions of the frontend, e.g. places where there is algorithmic heavy lifting going on. In such places there actually are input and output sets of data that are simulateable as test data: as in a multicolumn sort operation on a rendered list of items.

Of course unit testing could improve dramatically with new tools and paradigms. There is tremendous room for this field to grow. ES6 proxies, in particular, would be the key to autopopulating objects, therefore the key to self-mocking objects, and therefore the key to simplifying unit tests. If anyone knows how to get Phantom.js working with ES6 I would certainly be interested in working on improving Angular unit testing tools. Unit testing is definitely an area poised for spectacular innovation.

2. Static Typing

I’ve chosen to give typing the next highest spot on this list because it is perhaps the most abused good idea in the history of code. I’m going to therefore venture the most unpopular opinion of all: I don’t think statically typed languages are the future, or if they are, I don’t know that that’s a better future than what we have now. Why? The fact is that, like any engineering decision, there are benefits and drawbacks to the implementation of types. Types are of course amazing for some use cases—intellisense for example. Thus:

Good idea: statically typing some things

But if you’ve worked on Angular you know that types can present quite a stream of unecessary and useless build errors unrelated to actual application logic. There is a tremendous amount of overhead related to modules, ambient types, third-party libraries, data models that don’t match a type system, and boilerplate. Which is why I hold:

Bad idea: statically typing everything

Here is the always humorous (and linguistically precise) Rich Hickey, the creator of Clojure, explaining some of the problems with statically typed systems. He notes that information, of the type filled out in forms, isn’t naturally restricted to a type system of any kind. I would say that while typing is sometimes useful for getting metadata about libraries that are part of the framework itself, it shouldn’t be relied on to actually capture any errors flowing from application semantics, and should always be opt-in.

“But author of this blog,” you say, “so many experts, academic and profesional, can’t possibly be wrong about how to minimize risk.” Maybe, maybe not. Economic incentives and fear may lead to strange results, and when industries want to minimize risk without a clear, empirically proven, means of doing so, stranger things have happened. Consider the fact that to this very day technical analysts can’t tell a real stock from a fake one by inspecting its chart. Oh well, at least the prognostications talking heads make about “the market” sound scientific.

If we consider static typing as a tool like any other, it should be clear that its best use case (the case where it has not gone too far) is composed of two necessary conditions: in order for the error presented by a compiler to be maximally useful, the API of the typed construct must be (1) likely to change (2) without the knowledge of someone using the API. I’m not claiming typing can’t be useful outside of these cases, but that these two factors present the exemplary case of when the overhead of static typing is likely to pay off.

These two requirements are absent in third-party packages, since they should be moderately stable before we use them and we can lock the version down (at least until upgrading). Also, they aren’t present in our own code, since, provided we have a typical personality structure, our own code isn’t changing without our knowledge.

Ironically, then, the one area where static typing would be most useful is therefore a case where it is relatively neglected: ensuring compilation-time agreement between our own backend API, frontend queries, and frontend usage of returned values.

Our own backend API is likely to be rapidly evolving and doing so without our knowledge, since a communication boundary exists between frontend and backend development (typically these two tasks are performed by different teams or at least different people, and often on different schedules). So, all things being equal, the backend API should present the frontend with static typings for its endpoint results, and improper use of these should fail at build time.

Luckily, statically typing the integration boundary isn’t actually so hard if you are using Angular. If the backend provides an endpoint specification like Swagger, or is automatically annotated with some snazzy Java magic, all that is necessary is to parse this information in a new way (to create a Typescript interface), and at a new time (before compilation of the frontend Typescript code). Voila, you now have a statically typed integration layer, and all the pain of static typing suddenly is worthwhile. Now, instead of hoping and praying that the backend and frontend actually correspond, the frontend build will actually fail at compile time if the endpoint data is used in the wrong way. This can capture a lot of errors that would otherwise manifest as user complaints.

1. Functional Programming

Just kidding. When it comes to functional programming, there’s no such thing as going too far. The most that we can really say is that the terseness of some functional solutions makes code documentation more critical.

I mean, I suppose you could go to far. But one of the interesting arguments you could make about coding paradigms, at least if you have some personal affinity to one, would be to say that they should be taken to extremes. Taking a paradigm to the extreme allows it to be worked out completely. Haskellers seem to have some awareness of this with their motto “avoid success at all costs”.

I feel the same way about functional programming, at least as a research program. But when it comes to getting work done, I would have to say that even the idea of not having side effects must be tempered by the realization that the real world may make this goal unrealistic.

Wrapping Up

How might I characterize briefly what has been said here? Assuming I’m not just being contrarian for its own sake, maybe it’s worthwhile to ask whether there are any general ideas to tie things together. Is there any single common thread, aside from not wanting to subject ourselves blindly to fads? I suppose not, but if pressed I might call the main thread a preference for “minimalism”.

To recap, my general opinions or preferences are:

- All tools possess trade-offs.

- Code should strive to be minimalistic and functional, with comments serving as the basis of explanation.

- The number of syntactic entities should be kept to a minimum.

- Only a single primary language or series of constructs, and its most powerful and versatile sub-constructions, should be used throughout a system for consistency.

- Separation of concern is more important than code reuse, but this is hard to remember because creating abstractions is where the fun is.

- Behavior verification (types and testing) is by definition incidental to problem solving. It should therefore be used judiciously, and there is no need to implement it throughout a system. Assertions should concern a level of granularity that is realistic and should be focused toward areas that break as a result of communication barriers.

- Humans being able to reason about what is going on in a program is integral, not incidental, to program reliability. Therefore there is reason to believe that the solution for state management (reducing side effects) should be implemented everywhere, not merely topically.

- Because of inadequately characterized design goals, the state management solution may itself need to be implemented progressively.

- Process orientation is better than results orientation for both individual work and group dynamics.

Let it be known that I haven’t set out to describe Clojure. I haven’t even finished learning Clojure, hence the title of this post can’t possibly be “Why Clojure”. But writing this has made me realize just how much I sympathize with the ideas embedded in Clojure.

As I’ve said though, these are just my opinions. And I bet there are some things I’m misinformed about. Nevertheless, I think that most if not all of these are indeed examples of ideas that have gone too ar in frontend development.

Let me know what you think of this article in the comment section below!